A few years ago, the first emotional robot pet hit the market. Designed by the co-inventor of Furby, Pleo the Dinosaur is an adorable little beast, big eyes and feet, curious and playful and a little awkward… just like a baby dinosaur, except it comes in a box and is full of electronic innards. Kids can encourage it to seek out their positive reinforcement; or they can traumatize it with abuse. It imprints on its owners and enjoys being stroked. And it’s made of plastic.

Pleo — as well as earlier incarnations like Furby, Teddy Ruxpin, and even the Pet Rock — speak to a deep-seated human desire to relate with the world around us. It takes years for children to distinguish between the personal other (mom, dad, the dog) and impersonal other (plush toys, radios, statues)… and even as adults, the habit of projecting emotions on “happy” cars and “sad” buildings, of seeing faces in knotholes and napkins, never really goes away. It only makes sense that as the machine world becomes more and more a part of daily life, our technology’s rocket trajectory out of the spirited and sentient world of our ancestors would plunge right back into an age of cute computers.

Maybe personifying our electronics makes sense. After all, all evolving systems obey the same laws. With technology, essentially random innovations compete and cooperate under the selective pressures of the market, adapting to human wants. In that important respect, we might think of our relationship with machines as similar to our relationship with the vegetable kingdom. With his landmark book, The Botany of Desire, Michael Pollan gave the world a “plant’s eye view” of the coevolutionary relationship between the human species and domesticated crops like apples and corn. He argues that our story of bending these creatures to our will is only half the story; after all, we dedicate inestimable labor to their propagation and cultivation. We are as domesticated by plants as they are by us.

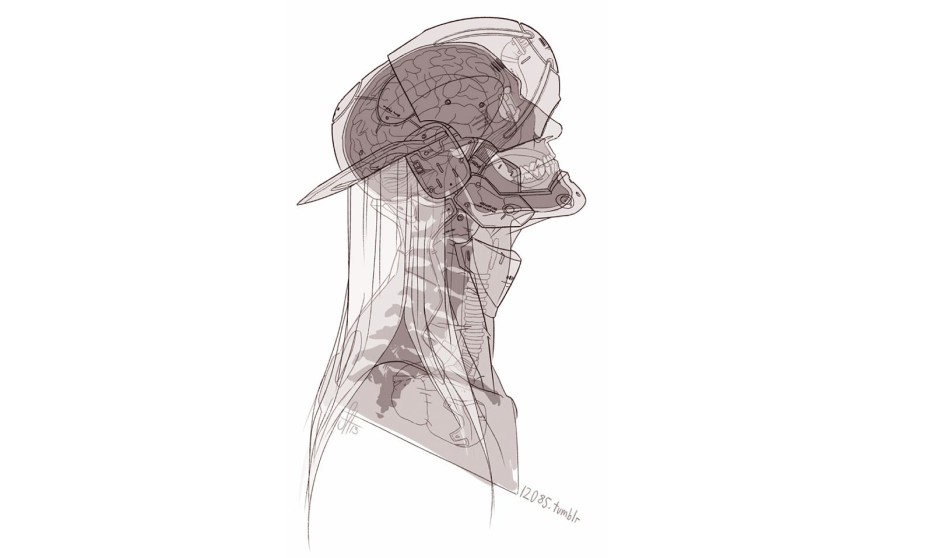

Likewise, Wired magazine’s founding editor Kevin Kelly’s latest book demands that we open a legitimate discussion about What Technology Wants. The conceit of modernity, that an increasingly sophisticated mastery of matter will eventually free us from earthly labor, ignores the fact that reality is more complex. The explosion of tech support and computer engineering jobs, the ever-growing work week, and the utter dedication to feeding Google and Facebook with our personal information that more and more of us display, all make plain: the more we use tools, the more they use us. Gradually, we have developed an intimacy with them as profound as the one between flowers and pollinating insects.

Not that there is any problem with this, any more than there is with our “exploitation” by dogs or cows, roses or bananas. Few people seem to mind the overt manipulation evident in how a cat’s meow has co-evolved with human emotional circuitry to more closely mimic the frequencies of a crying infant. (Neurons don’t complain about contributing their electricity to the holistic behavior of the brain…) The worldwide network of bloggers and other creatives might just as well be understood as stewards of an emerging mega-garden; or as farmers planting and then harvesting cultural experiences. (Is it any wonder we scrabble after fuzzy iPad cases with tails and invest our hopes and fears in the advent of emotional machines?)

From one angle we are, in Kelly’s words, “the sex organs of technology” — the mushrooms sprouting up from a global mycelium of routers and electrical wiring. From another angle, we live in loving mutuality with a vast distributed intelligence that constantly reshapes itself to better fit our desires. Those of us born before Pleo the Dinosaur might balk at the idea, but we are swiftly approaching a newly in-spirited world where living machines make philosophical questions of sentience irrelevant. As technology commentator Mark Pesce puts it:

Each one of us grew up in a world where people and pets were invested with a certain internal reality that bricks and blocks obviously did not possess. This is not true for our children. We have crossed a line in the sand, and there’s no going back: the current generation…have a growing expectation that the entire material world will become increasingly responsive to them as they learn to master it.

We might as well give this world the same love we might hope to receive from it. It starts by getting over our prejudice against machines, and embracing the inevitable marriage of the made and the born.

* hero image used from https://www.pinterest.com/pin/411586853422960549/

Leave a Reply