It struck me the other day that many people hold two beliefs that are incompatible with one another. Those beliefs are the idea that people have a fundamental right to life, and the notion that everybody should earn a living.

How are these two beliefs incompatible? People who believe that everyone should earn a living say ‘why should others get something for nothing when I have to work?’. But if you have a fundamental right to life, then you must have a fundamental right to access whatever you need to make life possible. Food, water, protection from the elements, these things should not have price tags attached to them, forcing you to submit to wage slavery or begging in order to obtain such essentials. They should be freely accessible, the common property of all people.

WORK OR DIE, NATURE COMPELS YOU!

Now, clearly, there is a practical problem with this sentimentality. Work has to be done to produce food, clean water, and pretty much all other essentials of life. The right to life is, of course, a purely human invention. There is no fundamental right to life built into the natural world. Were it not for our technological capabilities and social systems built up over millennia, human life would be like daily life for the rest of the animal kingdom: An ongoing struggle to survive in a world indifferent to suffering. We would have to strive to obtain the basic necessities of life. Well, not necessarily. Some percentage of the human race would be fortunate enough to live in an area that provides an abundance of food and clean water, and a clement enough climate to not worry about freezing to death during the winter. The hunter-gatherer lifestyle is a pretty decent one involving minimal work if you happen to live in a place where foodstuff and building materials are all readily available. But, of course, most areas of the world are not like that, demanding instead that animals and people alike work hard each and every day, if they are to survive to see tomorrow.

We have to accept, then, that people have always needed to work if they wanted to live. But, notice how the mentality is not that people must have a job of some sort and that nobody can get anything for free, like ideally this situation would not apply but hey ho this is how the world works, so we should just accept it. No, the argument is that people should not get anything for free and should earn their living. And that is saying something quite different to arguing that the world compels us to labor away. It is saying that, even if we could get away with not having a job but at the same time not face the prospect of material deprivation, it would be immoral for people to simply live their lives without earning a living.

I fail to see how this mentality is compatible with the notion of a fundamental right to life. It does not matter that this right exists only in our collective imaginations. Plenty of things exist in our world which are entirely a product of our minds with no objective existence outside of human thought. If there were no people in the world there would be no films, no music and no religion. But there are people in the world and those things- along with an uncountable list of other cultural creations- exist because we willed it. We can believe in the right to life, and work to make it a reality. But there can be no fundamental right to life along with a belief that nobody should get something for nothing.

RISE OF SOCIAL SECURITY

Technological progress and societal organizations have made our lives much easier than they were in previous generations. In the past, food production took up the vast majority of most people’s time. Today, as it is cleverly explained on LandrumHR.com, agriculture employs only a fraction of the numbers of people that used to be employed in order to grow crops and raise livestock. For our ancestors, preparing dinner took up most of the day. Those of us fortunate enough to live in wealthy countries with access to supermarkets, convenience food and microwaves can have a meal ready to eat within minutes. And our notions of retirement as a decades-long holiday as due reward for all those years of loyal service to the world of employment is a recent innovation. For most of history, people worked until they were fit only for the deathbed.

In affluent countries it is actually not the expectation that everybody must have a job or die. The elderly, the disabled, children, they are not expected to either be in employment or to live grim lives of hunger and material deprivation. Society has established systems of child support, welfare, and pensions which support these members of society without forcing them to go out and get a job. Not everywhere. Some parts of the world still have child labor, still require people to work right up until their death and still condemn the disabled to beg on the streets to secure enough money to pay for their next meal. But it is obviously true that in some parts of the world if you are below or above a certain age, or you have a disability which makes it too much of a struggle to function in any job, you are not forced to live in deprivation.

Personally, I see this as progress. But I suspect there are others that do not. People who see any form of socialism as an attack on liberty and spit blood at the very notion that any of their or anyone’s earnings should be used to fund the lives of those not in work, even when some people’s salaries ensure them a personal fortune orders of magnitude beyond anything required for material comfort and they would still be rich by any decent measure if 90% of their savings were taken and distributed among the nation’s children, disabled, and elderly.

Now, maybe these people would say I am misrepresenting their stand here. Maybe they would say, ‘look, Extropia, we are not saying that the child labor is right, that state pensions ought never to exist, and that the disabled should get no help from the government. We are just saying that anyone who is of working age and fit to work should be in a job, and contributing to society instead of just taking from it’.

This attitude assumes that there are people in the world who are not in employment simply because they are too lazy to be in a job. And you know what? Such people exist. There are benefit cheats who know how to work social systems and extract money to which they are not entitled. This, needless to say, means there is less money than there otherwise would be to give to the unfortunates of society who, due to genuine disability or ill health, really cannot be in work, just as there is less money due to the most affluent hoarding it in vast personal fortunes. We ought to put pressure on anyone who is taking a lot more than they really deserve or need, regardless of what social class they are in.

THE DIMINISHING NUMBER OF JOBS

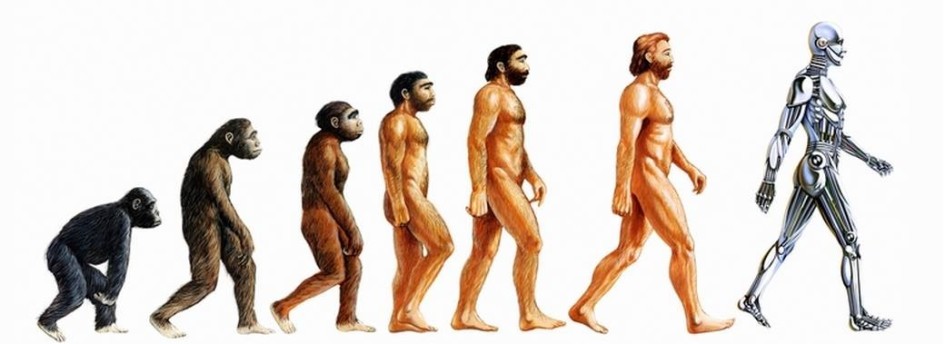

But we should also acknowledge that there are people whose sole job is to close down employment opportunities for other people. Who are those people? Why, the engineers of automated systems that replace manual labor, the software writers who design programs that do white-collar office jobs. Both robots and artificial intelligence systems are becoming less inflexible, and therefore more able to function adequately in a wider variety of tasks. It takes minimum skill to show a robot like Baxter how to perform any manual task that is in reach of its arms, no highly trained technician is required. And bare in mind that a Baxter is to robots what 70s and 80s Pcs were to computers. In the beginning, computers were bulky, expensive machines that required rare skills to operate, and were useful only in a very limited range of services. These mainframe computers evolved into minicomputers like the PDP1 (mini as in not taking up entire rooms, but still pretty big- the PDP1 was as big as a domestic refrigerator), and- by the 70s and 80s- into desktop computers, small, cheap and user-friendly enough to be of service in offices, factories, and eventually, our homes. Today, of course, computers are absolutely ubiquitous and our entire economy is dependent on these machines performing jobs which were either once the responsibility of people, or not performed by anyone due to humans being fundamentally incapable of doing such work.

If robots are about to become as ubiquitous as computers were in the 80s and 90s or today, then that has to have serious consequences for notion that people should earn their living. Bare in mind that, during the Great Depression, 25% of people were out of a job. Given the capabilities of robots and intelligent software being demonstrated in R+D labs around the world and piloted in some real world scenarios, it is perfectly reasonable to suppose that pretty soon 45% of all jobs will be lost to automation. It is always tempting to believe one’s own job is immune to robotic takeover, or that technology will always create new jobs. But, as CGP Grey pointed out in his short documentary ‘Humans Need Not Apply’, if our ancestors had thought ‘more and better technology means new jobs for horses’ we can see that they were simply wrong. Today, there exists only a fraction of the number of working horses. They are simply unemployable, not economically viable thanks to the ‘horsepower’ we get from our machinery. Jobs for horses have not been reduced to zero. The Amish and developing world nations use horses or oxen to pull their farming instruments, we breed horses to race, the police use horses, England’s spectacle of trooping the color would not be the same without those magnificent drum horses, but these amount to a paltry number of working horses compared to what there used to be.

Similarly, human employment may never be reduced to zero. There may always be some jobs which nobody or nothing has figured out how to automate in a cost-effective way, or jobs which we could automate but choose not to, feeling such work ought to be done by people and not machines. Childcare, for instance, may be a job that ought not to be offloaded to machines (though we may well want to make the task easier through machine assistance). However, such jobs must surely amount to a tiny percentage of all employment opportunities that exist today, so once all jobs except those rare un-automatable jobs are gone (assuming that there actually are jobs that could not or should not be automated) the stark truth is that most people will be as unemployable in the job market as a horse is.

A REAL RIGHT TO LIFE.

If we have succeeded in achieving that level of automation, and have blue-collar robots doing most if not all manual labor, white-collar AI doing managerial, legal and financial work, and the economy is pretty much fully automated, or at least predominately automated requiring only a tiny percentage of the population to do anything, then for heaven’s sake why not extend the benefits system to support not just those who cannot work due to their age or ill health, but those who were made unemployable through no fault of their own? Why make them feel guilty about not having a job when the number of jobs still open to humans has been so drastically reduced there are more people out of work than there are vacancies available to be filled?

Why not, instead, see the ephemeralization of technology- its ability to enable more work to be performed with increasingly less effort- as a golden opportunity to make reality the stirring words of the American Declaration of Independence, that we hold as self-evident truth that all people are endowed with certain unalienable rights, such as life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. The fundamental right to life means the right to have access, without restriction other than greed which restricts accessibility for others, to the material resources required to make life, liberty, and happiness possible. With our upcoming technological capabilities we could make it a reality that nobody need be in a job in order to have a decent life, and in such a world the attitude that people should earn their living would be objectionable by any decent ethical standard.

* edited for spelling.

Leave a Reply