A brief review of existing visions for alternative political systems

Introduction

Last year’s establishment of the Transhumanist Party in the u.s. has sparked much activity in Europe towards the same goal, and it seems likely that the trend will spread across the planet within the next few years. This begs the question of the ‘vision thing’ as G.H.W. Bush once called it.

Unlike the general movement which is under little pressure to develop a common goal about what kind of society and political, economic and social model or models it wants to pursue, and indeed encompasses a wide range of ideas on the topic, political transhumanism will be asked the question and must develop at least some vague models, and ultimately concrete programs, to work toward.

This task is complicated by these factors among others:

- Participants in electoral democracies must adhere to the rules under which these systems operate, which also vary from country to country, despite the question of the desirability of these rules, and the likelihood that they will, perhaps profoundly, change as a consequence of accelerating advancement of technology and its effects on social structures anyway. But it is the essence of transhumanism to not only anticipate these changes but attempt to control them toward maximising benefits for the planet.

- These changes bear a high degree of unpredictability, so the vision is necessarily a moving target. Nonetheless at least foundational principles and a general direction have to be made identifiable, and these will have to avoid being in conflict with local constitutional conditions as well as voter acceptability.

- Most self-declared transhumanists entertain already individual visions which vary widely, sometimes enough to constitute incompatibilities, and those who participate in party politics must work to at least arrive at common denominators.

This process has barely begun, which is why i decided to assemble some existing models and fragments that appear suitable as building blocks for debating and developing visions that can be commonly agreed upon.

A – Science Fiction

Over a century science fiction has established itself as a rich source of inspiration for technological and social innovation as it provides complete freedom from the restrictions of current reality for developing and fleshing out possible scenarios and offers an abundance of ideas and models. Here i want to restrict myself to discussing only the one that is probably most widely known: Star Trek.

Those familiar with the various productions will know that the protagonists act within a world characterised by material abundance and minimised social conflict. Yet the environment is far from a perfect utopia. Evolution continues but mostly in regard to technology and little in terms of psychology and biology, problems with technology persist and conflicts mostly with other ‘species’ keep erupting, mostly at the periphery of the terrestrial federation. While a comprehensive social model is never presented there are possibly enough indications of its elements to allow to reconstruct a somewhat comprehensive picture. One such attempt has been undertaken by Rick Webb.

In his view,

The federation is a proto-post scarcity society evolved from democratic capitalism. It is, essentially, European socialist capitalism vastly expanded to the point where no one has to work unless they want to.

It is massively productive and efficient, allowing for the effective decoupling of labor and salary for the vast majority (but not all) of economic activity. The amount of welfare benefits available to all citizens is in excess of the needs of the citizens. Therefore, money is irrelevant to the lives of the citizenry, whether it exists or not. Resources are still accounted for and allocated in some manner, presumably by the amount of energy required to produce them (say Joules). And they are indeed credited to and debited from each citizen’s “account.” However, the average citizen doesn’t even notice it, though the government does, and again, it is not measured in currency units — definitely not Federation Credits. There is some level of scarcity — the Federation cannot manufacture a million starships, for example. This massive accounting is done by the Federation government in the background.

While it is not knowable that this socio-economic model did evolve from ‘democratic capitalism’, the similarities between it and social democratic capitalism are large enough, the few references to the transition period, which took no more than a couple centuries, make no mention of disruptions major enough to have caused substantial deviations, so that this is a real possibility. Apparently the only major intervening change is the substantial advancement of technological capacities which is already underway and accelerating. This of course is a very optimistic scenario according to which today’s humans, if existential catastrophe can be avoided, just have to carry on as now.

But does this system of abundance really work well? For the most part yes, but within limits. On the individual level it is impossible to go overboard because

If they go crazy and try and purchase, say, 10 planets or 100 starships, the system simply says “no.”

Webb explains that this occurs rarely if at all by assuming strong ‘social pressure against conspicuous consumption’, but it seems more likely that it is due to the fact that nobody will be impressed by it when everybody has what they need and more, than because of social pressure which is likely to provide motivation to disregard it. He points out that locally crises and disasters can and periodically do occur. These can be caused by unforeseen environmental changes or interference by nonhumans. Help is usually dispatched quickly but does not always arrive in time, and sometimes it is already too late by the time information reaches Starfleet.

In the current discussion the scope is usually limited to Terra. The complications and unpredictabilities resulting from encountering and reacting to nonhuman interference are ignored, and for good reasons, as there is simply no way to know what benefits or threats it may bring. Most existential threats that can be anticipated are home made. Biospheric warming has already limited effects on politics, economics and technology; the only extraterrestrially caused events that warrant serious efforts of preparation are meteoric and cometary impacts. It is therefore unnecessary to explore this aspect any further.

There is a lot of trading going on between humans and nonhumans, which presumably accounts to a degree for the abundant conditions in the terrestrial domain. The Enterprise occasionally finds itself needing certain materials to carry on that have been lost, destroyed or consumed and they are often obtained through bartering from established nonhuman systems or freelance traders or smugglers. The wild card in these scenarios appears to be replicator technology. In the current debate additive manufacturing is often pointed to as a solution for self-sufficient resourcing, which is incorrect. 3D- printing will lower production costs mainly by eliminating labour expenses, but raw materials, ‘ink’, will still have to be synthesised, mined or grown. A much larger step will be alchemy through nanotechnology. My conclusion was that this is the method used in replicators, and if so it is unclear why the ship would be dependent on bartering. Some reviewers however go a step even further and claim that replicators create matter from energy, which appears highly unlikely given how much energy would be needed according to Einstein’s famous formula just to constantly feed a thousand people. But then i do not know how and how much energy can actually be generated by warp drive technology. As long as humans are confined to Terra it would appear that nanotech will be sufficient to provide the material basis for abundance.

Quite a few essays and articles about Star Trek and its economics can be found, and a few caught my attention for various reasons.

One by Greg Stevens makes an interesting and quite obvious connection to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and says:

If human endeavours are seen as advancing up this noble ladder of advancement, then any society where all of the basic low-level needs are met would obviously be left to while away their time exclusively on love, self-esteem, and self-actualisation.

Near the end of his article Stevens points to this possibility:

One of the biggest fears that comes up in this discussion is the simple fear of pranks and mischief-makers. Mischief-makers of this kind are largely absent from the Star Trek universe, but they are a very real component of humanity.

He quotes from Rudy Rucker’s “Realware” and presents some examples of his own, illustrating the possibility to create anything out of thin air and concluding:

Some people will want to band together and perform great creative deeds for the betterment of humanity ….. But some people – maybe even most people – will want a thousand-ton turd.

In this extrapolation he ignores the probabilities indicated by accelerating evolution of human psychology, but if this were to become a real problem there will be technological solutions to it.

In his piece “The Star Trek Economy Thing” Joshua Gans, after dealing with the problem of how to measure the value of goods and thus G.D.P. growth, points to the changes of terrestrial economy caused by the massive increase in military production after the first Borg invasion. While it remains rather unlikely that Terra will be invaded by the Borg, or will be able to resist, anytime soon, it is important to expect the unexpected and gear some of the wealth derived from the coming abundance toward dealing with unanticipated high impact events.

At the conclusion of his article Fred E. Foldvary writes:

Each person’s heritage, values, and personality are respected. While this is relatively easy to achieve in the organizational order of a ship, to do this on a galactic scale requires universal liberty where each person, regardless of species, has an equal right to do whatever does not coercively harm others.

Ship captains repeatedly talk about cultural evolution as if it is following along the same lines for each ‘species’. But that this is not necessarily so is shown most starkly by the Borg but also others like the ‘extragalactic’ Species 8472. I do not even think that all posthumans will want to continue evolving uniformly, as we already are confronted with incompatibility among human cultures to which my proposed solution is habitat separation, an issue i will address elsewhere.

The strongest connection between Star Trek economy and current theory of economics is made by Andrew Leonard in his Salon article “The utopian economics of Star Trek”. Starting out from J.J. Abrams’ 2009 film ‘Star Trek’ he points to the explicit reference it makes to new growth theory as laid out in Paul Romer’s 1990 paper “Endogenous Technological Change” (download). Not being an economist i am in no position to technically evaluate its merits, but it has found wide acceptance and seems to be definitely worth studying in the quest for economic models compatible with transhumanist thought. For non-experts like me easy introductions are offered in WP and by Tyler Cohen’s and Alex Tabarrok’s brief video introduction.

In conclusion it appears that models presented in Star Trek and other science fiction creations, many of which are much further removed from the present, are of limited value in developing a politico-economic transhumanist theory. By their very nature as stories to be told they inevitably focus much more on the what than on the how. However they contain plenty of ideas that can be useful in defining transhumanist goals.

B – Transhumania

In the very near future Transhumania is created as an extraterritorial independent city state floating offshore in international waters. Zoltan Istvan has used this device for the plot of his novel “The Transhumanist Wager” but also as an illustration of his idea of a transhumanist polity; therefore it gets a fair amount of the author’s attention in that he outlines principles and practices of living and working together in a transhumanist community.

While quite a few reviews of the book itself have been written, not much has been on this particular subject yet. There is an interesting piece by 33rdsquare which deals with the figure of Jethro, the main protagonist and most radical of the transhumanists, but it becomes clear in the course of reading that there is no real difference between his person and the political system he implements, and i will refer to it later.

In the press conference where Jethro presents Transhumania to the rest of the world, he says the following:

Ladies and gentlemen, behind me on the screen is a picture of Transhumania, the seasteading transhuman nation where scientists, technologists, and futurists carry out research they believe is their moral right and in the best interest of themselves. We are on our way towards attaining unending sentience and the most advanced forms of ourselves that we can reach, which is the essence of the transhuman mission.

And later:

On Transhumania, we are all one-person universes, one-person existences, one-person cultures. Bearing that in mind, we may still live or die for one another: for our families, for our children, for our spouses, for our friends, for our colleagues at Transhumania—or for those whom we respect and for whom we care to reasonably live or die. We will not live or die for someone we don’t know, however. Or for someone we don’t respect. Or for someone or something we don’t value. We will not throw away years of our lives for uneducated consumers, for welfare-collecting non-producers, for fool religious fanatics, or for corrupt politicians who know law but don’t stand by it or practice it.

This does not contain much information on the topic, but provides a good insight into the intellectual atmosphere in which Transhumania is conceived and created. Only the first sentence of the second paragraph hints at principles of social organisation. Clearly the individual is the basic element. This one-person universe can submit to more general collectives such as family and friends, implied by one’s willingness to die for them, and the term ‘submit’ is used here not in the sense of subordination but that of integration. But i question the verity of including colleagues here. If this refers to colleagues in general it seems plausible in the sense that they have all submitted themselves to the idea and cause of Transhumania, have integrated into it and thereby become subject to the willingness to die for Transhumania itself. But if it regards personal disagreement or conflict such a decision would have to be taken under the rules of utility as described in the following quote that closes Jethro’s address, and will be further discussed within the topic of humanicide:

We will invite you to join us: as friends, as colleagues, as comrades. And we will trade value to each other to gain what we want. We will discriminate against and judge each other on the basis of whether we offer sufficient utility to one another or not. There’s only one quintessential rule on Transhumania: If you don’t add value to the transhuman mission, if you are inconsequential or a negative sum to our success, then you will be forced off and away from our nation.

The political structure of Transhumania does not amount to much more than derivation from Jethro’s logic, which i consider to not always be compelling, and the social structure during the island days is firmly based on the business principle: benefits in exchange for work. This changes later when after a military confrontation with a coalition of established governments is won by Transhumania which then proceeds to govern all planetary affairs. The underlying principle is a hierarchical meritocracy with Jethro, bearing the most merit, at the top.

All reviewers appear to agree that when Transhumania takes on global rulership Jethro starts using his position in dictatorial manners. I tend to disagree. The project has been run this way since its inception, only until now he never encountered any resistance. The following quotes illustrate the way in which his transhumanist ideology remains paramount:

The Transhuman Revolution seeks to transform the world into a transhumanist-inspired planet. Transhumania aims to fulfil that goal in order to harness the Earth’s resources and to unite with those millions of people on the outside who can, and want to, help us accelerate the greater transhuman mission…

Jethro turned from the ocean and stated firmly to the leaders of Transhumania, “We want to teach the people of the outside world, not destroy them; we want to convince them, not dictate them; we want them to join us, not fight us.

In the following i sense an almost fascist attitude of contempt: “If you weren’t an intellectual with progressive thinking and creative futuristic ideas, you were no one”, which is somewhat ameliorated by the fact that mandatory and free education is provided.

And the reference to Earth’s resources betrays colonialist impulse:

The Transhuman Revolution seeks to transform the world into a transhumanist-inspired planet. Transhumania aims to fulfil that goal in order to harness the Earth’s resources and to unite with those millions of people on the outside who can, and want to, help us accelerate the greater transhuman mission.

And here he surprisingly commits a grave logic error, taking his reasoning to absurd conclusions:

The optimum transhuman trajectory of civilization is that which creates the most efficient way to produce omnipotenders. Currently, the best way to accomplish this is to achieve as expediently as possible the highest amount of productive transhuman life house in the maximum amount of human beings; however not all human beings will be a net-positive in producing omnipotenders. Any individual who ultimately hampers the optimum transhuman trajectory of civilization should be eliminated. The Humanicide Formula addresses these issues directly. It determines whether an individual should live or die based on an algorithm measuring transhuman productivity in terms of that individual’s remaining life hours, their resource consumption in a finite system, and their past, present and potential future contributions.

Besides the inane concept omnipotender, meaning an almighty one, which is an unrealistic idea and contributes nothing to the story, there is no need for such a formula in an abundance based society. This seems to be more of an expression of dislike of, and contempt for, those who show no interest in becoming ‘omnipotenders’, and it implies totalitarian control over the behaviours of individuals.

This is addressed by 33rdsquare as well:

Knights even describes how TEF should make people try to act like computers, to explore and even attain a “cold precisionlike morality” and a “harsh machine-like objectivity.” Among the controversial ideas Knights and his fellow transhumanists act out would transfer those billions from programs that fund society’s most vulnerable — or as Knights says, “lazy welfare recipients,” “mentally challenged, “uneducated repeat criminals” and “obese second-rate citizens bankrupting our medical system”.

But Jethro manifests more agreeable aspects of his personality. Here he shows a degree of transparency rarely seen in current governments:

Every one of you is to go to your teams and staff today, and tell them the same thing I have told you: war is imminent. You are also to offer them the same opportunity to leave Transhumania on the same terms I have given you. Tell them everything exactly as I have told you just now.

After 17 years of undivided rule he announces ‘democratic elections’. At this point transhumanism has been firmly established and accepted, and the presidency smoothly goes to his closest associate. This raises the question of what criteria should apply for participation in ‘democracy’, a topic to which we will return later.

As we have seen there is not much in the rules by which Transhumania is governed that is applicable to the foundations and policies of current transhumanist parties. This is quite surprising but can be explained by the way in which transhumanism comes to power in the novel and by Jethro’s l’état c’est moi approach. Meanwhile in the real world Zoltan is pioneering the transhumanists’ hopefully not too long march through the institutions.

C – Neue Slowenische Kunst

NSK or Neue Slowenische Kunst, which is german for New Slovenian Art, is an art collective based in Lublijana. It was founded in 1984 by the multimedia group Laibach (established 1980), the visual arts group Irwin (1983), and the theatre group Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre (SNST) (1983–87). Further groups have joined since then. In 1992 they founded NSK State in Time, which is described on their website:

The State is conceived as a utopian formation which has no physical territory and is not identified with any existing national state. It is inherently transnational and describes itself as ‘the first global state of the universe.’ It issues passports to anyone who is prepared to identify with its founding principles and citizenship is open to all regardless of national, sexual, religious or other status. It now has several thousand citizens across numerous countries and all continents, including a large number in Nigeria. The NSK State itself is a collective cultural work, formed by both the iconography and statements of its founders and its citizens’ responses to these and to the existence of the state. It is also part of the wider ‘Micronations’ movement which has grown increasingly visible and received growing critical and theoretical attention in recent years.

It is clearly not directly applicable to current or future realpolitics transhumanist parties are dedicated to, but still can serve as a model to work toward in the long view.

Several very interesting articles have been written about it, most putting greater emphasis on its artistic implications than the political ones, even though the two are inseparable.

Conor McGrady writes in The Brooklyn Rail:

A full working group session also examined the question of whether the NSK state should or should not consider itself a micronation. Loosely described as “independent nations or states, but which are not recognized by world governments or major international organizations,” micronations usually exist as social or political simulations. On this issue delegates were unanimous. It was argued that the NSK state transcends micronations, in that for the most part they limit themselves to outmoded forms of government, mimicking fiefdoms, monarchies, and other feudal structures. As the “first global State of the Universe,” it was suggested that the state relate to micronations in a paternal fashion, rather than build fraternal ties.

On the influencers site i found this quote:

The artists who form the collective Irwin are the visual biographers of NSK: their work, framed within the tradition of totalitarian regimes, reappropriated the supremacist symbols of the Eastern European Block to construct their own identity as “state artists”, faithful to a strict collective discipline. They opened consulates, designed badges and distributed passports for the NSK, a “state in time” that takes the paradoxes of state identity to an extreme in order to ultimately reveal a glimpse of the hidden face of existing ideological structures.

The most interesting view is presented by Gordan Djurdjevic in his article ‘Crossing the Wires: Art, Radical Politics, and Esotericism in the Project of Neue Slowenische Kunst’ on the academia site, where he explores the esoteric dimension of NSK, which he introduces with two quotes:

- “All art is Magick” – Aleister Crowley

- “All art is subject to political manipulation … except for that which speaks the language of this same manipulation” – Laibach

In 2005 MIT published an extensive treatment of Laibach and NSK by Alexei Monroe under the title of ‘Interrogation Machine’.

Certainly transhumanism will have to develop an artistic foundation, especially in the context of party politics and propaganda. NSK can provide interesting and valid ideas, and should be studied.

D – Zero State

Zero State is an emerging trans-national, virtual state. On its website it is presented as follows:

The Zero State (ZS) community works toward the establishment of a VDP (Virtual/Distributed/Parallel) State or “Polystate” committed to Social Futurism and the WAVE Principles.

These terms are explained there subsequently, with the exception of ‘Polystate’ which may still be in flux; it has no WP entry yet, but here Poly- and VDP state are equated. We will look at Polystate separately later on.

On its site there is a FAQ section that describes its general ideas and the possibilities of participation, but not much is said about either its internal structure or its ideas for the organisation of the world at large. However in an article on the IEET site by Amon Twyman, who is the founder of ZS, entitled “The Social Futurist policy toolkit” he says: “It is my intent that this toolkit should form a kind of bridge between the broadest, most general level of political discussion on the one hand, and the development of specific policies for local groups on the other”, and lays out the following six policy categories:

- Evidence, Balance, & Transition

- Universal Basic Income & LVAT

- Abolition of Fractional Reserve Banking

- Responsible Capitalism, Post-Scarcity, & Emergent Commodity Markets

- Human autonomy, privacy, & enhancement

- Establishment of VDP (Virtual, Distributed, Parallel) States

It would be redundant to explain these categories here, and i highly recommend reading the original text on the site. Another promising source may be the book “Zero State: Year Zero”, which to read i did not have enough time. Another source worth mentioning here is the technoprogessive declaration conceived during the TransVision conference of 2014 and mentioned here by James Hughes.

While far from a comprehensive program, an internal constitution or a vision of how to optimally organise local, national, or virtual association, this toolkit does in fact deliver the “the broadest, most general level of political discussion”, which can be the basis for any and all of the above. The principles underlying these policies can be applied to all political activities. Besides the Transpolitica manifesto, which is actually ideologically very close to, if not identical with, Twyman’s social futurism, and well worth studying, this is in fact the most suitable material i have come across in my search for transhumanist political principles. But that is no accident as ZS is clearly a transhumanist organisation de facto, if not explicitly, and it has begun developing long before transhumanism entered the political arena.

E – Libertarianism

There are two areas where a strong connection between transhumanism and libertarianism exists.

History: early transhumanism, namely extropianism (now extropism), grew, at least in part, out of the 60s counterculture, a confluence of various movements such as those who work for equality before the law (race, gender, wealth, age) and those who work for mental, physical, and social self-determination. Many among them declared themselves to be libertarian, quite often reflexively as a reaction to the restrictive policies used against them. Libertarianism was almost the countercultural default position in those days.

Economy: many of the people who dream up, develop and produce the technologies that are essential to transhumanist thought are unsurprisingly entrepreneurs and capitalists, and a sizable number among them are libertarians, trying to minimise government influence on business activities.

Since the turn of the century an increasing influx of a variety of new ideas and people into transhumanism is underway, and now libertarians are a large minority within the movement.

Even though the core idea of libertarianism is that of individual freedom with an emphasis on protection against intrusion by ‘authority’, this has often been expanded and altered. Within the economic domain it often refers to the freedom of business activities and strongly overlaps with neoliberalism. Other variants such as socialist, anarchist and cooperative libertarians promote freedom from corporate as well as governmental interference.

Politically libertarianism plays a significant role mostly in the u.s., while in Europe it is more of philosophical interest. Because of the diversity in the usage of the term, it is not easy to find common libertarian principles that could apply to transhumanism.

However there is an extropian manifesto that contains the following policy principles:

- Endless eXtension – perpetual growth in accord with biological and technological evolution

- Transcending Restriction – “abolish all restrictions imposed by religion, protectionism, segregation, racism, bigotry, sexism, ageism, and any of the other archaic fears and hatreds”

- Overcoming Property – reform of “archaic, out-dated human laws that govern possession by improving and/or annihilating terms such as ownership, copyright, patent, money and property”

- Intelligence – “The most valuable material in the universe is information and the imagination to do something with it”

- Smart Machines – “attainment of Friendly Artificial Intelligence. We promote the development of robots, computers, and all machines that can emulate human thought, copy minds, and attain intelligence that exceeds human ability”

These are explained further on that site. They appear to be quite compatible with those of ZS mentioned above, again unsurprisingly. Another concept that i find very useful is that of the Proactionary Principle explained on the Extropy Institute’s site.

F – Socialism

Even though socialist ideas have been promoted since long before Karl Marx, his version is often associated with the term. Founded in materialism that holds that history is driven by the changing material base, the economic conditions, which determines the superstructure, society’s culture and politics, it is based on the principles of collective ownership, compensation by contribution and production for use.

While for Marx socialism was a transient period leading by historical necessity to communism, the various forms of socialism we see today, including social democracy, would be described by him as reformist. He made explicit this distinction in his 1848 Communist Manifesto.

Unfortunately he did not foresee the development of the power of the media we see today, which does a lot to obscure the perception of real class differences, especially in the u.s. where the term ‘class’ has been successfully banned from the vocabulary in order to keep up the pretence that class does not exist, which leads almost half the population to regularly vote contrary to their own material interests. He also ignored, understandably, the fact that the traits that lead humans to capitalist behaviour in the first place, namely hoarding and raiding, control and violence, are anchored deeply within the genetic code as they proved to be conducive to survival during a long period of human history. This was the main reason that the only real experiment to implement his model three decades after his death, the soviet union, showed signs of failing even under Lenin and turned into an imperialist ‘thugocracy’ under Stalin, from which it never recovered. Thus socialism as it exists today is quite distinct from the marxist idea and comes in a wide range of variations which can also be quite distinct from each other.

As it would exceed the scope of this writing to explore the many variations of socialism that today are alive and, because of the accelerating excesses of capitalism, increasingly kicking, it shall suffice to point again to the above quoted article by Twyman. At least points 2, 3, and 4 in his policy toolkit imply a more or less profound reform if not abolition of capitalism. In fact the article also includes ‘A note on Marxism’, in which he says:

Social Futurism does not deny the Marxist analysis of the problem, but seeks a staged transition to a post-Capitalist society which does not attempt to undermine the entire basis of our current society in a single move.

I completely agree with this position, but in this context point out that his transhumanism, or ‘social futurism’, is one form, in my view the most advanced, of what Marx would have called ‘socialist reformism’.

Even the third point in the extropian manifesto ‘Overcoming Property’, far from being libertarian as understood in the u.s., is in complete contradiction to the foundation of capitalism.

In closing i must point to the above mentioned principle of ‘production for use’ as opposed to production for profit. As the latter takes an increasing proportion of value out of the economy and makes it disappear into a finite holding of unproductive land and real estate value as well as an infinite holding of financial or virtual value, transhumanism, which is based in reason, but also any reasonable economist, will see virtue in this principle.

G – Anarchism

Like socialism anarchism is a historic phenomenon with close links to the former that also is alive today in theory but much less in practice of political significance. There are no anarchist governments in existence and no significant anarchist parties, the latter actually being a self-contradictory concept. Another problem is that anarchism in much of public perception still carries terrorist connotations.

And like socialism it also manifests a wide range of sometimes contradictory variants, too many to list in this context, but a fairly comprehensive overview can be found here.

However there exists an explicit form of transhumanist anarchism with its own manifesto. It claims to be based on the Transpolitica manifesto, from which it distinguishes itself by introducing the concept of vanguardism:

Vanguardism traditionally conceived of a small group of people who value a socialist state to guide the working class (proletariat) away from the tyranny of the capitalist-state and the few who run it (bourgeoisie)”.

This is sensible only under the premise of misidentifying socialism as leninism, stalinism or some other such manifestation, and adds nothing of value to the discourse.

While the manifesto is perhaps the most detailed presentation of transhumanist policy ideas, and i essentially agree with its intention and recommend it as a rich source of material and inspiration, i see two major flaws with it.

To associate transhumanism with anarchism, and anarcho-syndicalism and libertarian socialism in particular, instead of promoting these ideas simply as transhumanist policy principles, is a tactically unwise move that will not find much resonance in populations of currently existing polities. Likewise including the Fermi paradox is unneeded baggage and the question “Have millions of civilisations gone extinct because they could not realize such a [anarchist] society?” is naively self centered and showing an untranshumanist lack of imagination.

It appears to be in disagreement with engaging in electoral procedures within current systems that even allow for such an option. “Said reform rarely happens as parties become interconnected with the current neoliberal system”. My conclusion is not inescapable, but a political party by its very nature has to be connected with existing systems, none of which are by definition neoliberal, neoliberalism being just the current marketing device of capitalism.

H – Democracy

Even more so than socialism and anarchism, the term is applied in a myriad of ways, ranging from the just mentioned anarchism through western systems to the DPRK. Everyone, including transhumanism, and even Jethro Knight’s version, wants to be ‘democratic’ because of the populist attraction it has assumed over the past two centuries. In truth the rule of the people has remained elusive, and personally i object to it at least until ‘the people’ have, through voluntary, if possible, genetic reprogramming or otherwise, purged themselves of the obstructive tendencies acquired in the course of human evolution. But a more plausible solution appears to be the delegation of policy decisions to future machine intelligence altogether. However neither is currently or in the immediate future available and the idea is beyond our current concern; my point here is that like everything else, the idea of rule by the people should be questioned.

But if the ‘will of the people’ is to partake in the generation of political decisions, there should be more efficient ways to accomplish this than through representative bodies, despite the fact that that is currently the only model being practiced. Most people do not feel like they have any real influence on politics, especially on the state level, and the clearest indicator for this is the often quite low rate of electoral participation. I shall here present brief descriptions of some alternative approaches.

1. Delegative Democracy

There is precious little information out there on this concept despite it being very plausible at first glance. The best i could find is Bryan Ford’s 2002 paper, and apparently its last two sections are still under construction. In 2014 he published ‘Revisited’, which contains some further links. Both are here.

The idea is that each voting right holder can choose to delegate his vote, preferably to a person he trusts and knows to hold similar views on the matters of concern as himself, or to become a delegate himself. This principle is repeatable so that the next level will always be comprised of fewer delegates than the previous. Each delegate is afforded a degree of influence corresponding to the number of votes he represents. The aim is to combine the principle of direct democracy with the practicality of representative democracy.

Advantages are among others that voters, even those who have no time or inclination to study the issues in question, can feel that their votes are not wasted, and that the cost for entering the process is low. The WP entry contains a more detailed list, and Ford’s paper discusses ideas on practical problems and solutions.

Software solutions for implementing the systems have been developed and European Pirate Parties are using them. There is also a brief and quite superficial video introduction.

The model is certainly one to be explored, discussed and tested.

2. Deliberative Democracy

Beyond the question of how to best recognise and realise voters’ intentions, this model is concerned with the quality of those intentions. Valid decisions can only be arrived at through explicit deliberation free of the influence of prevailing power structures.

The main forum promoting this view is the Center for Deliberative Democracy (CDD) at Stanford and its website contains research papers, events, briefing documents, questionnaires, a downloadable toolkit, case studies, videos and press publications.

The case studies always involve deliberative polling, whereby random samples of people, considered to be statistically representative, convene to intensely deliberate certain issues under the guidance of trained moderators. They are polled before, during and after their discussions and considerable changes in content and quality of opinion are often found.

Currently the main proponent of the concept is James S. Fishkin, director of the CDD. He and others present a series of videos that will give the reader a good idea of the theory and current practice of deliberative democracy.

In his 1985 book ‘Is Democracy Possible?’, last updated in 2014, John Burnheim presents a much more profound approach, based on rethinking the current social and political structures quite radically.

He envisions the obliteration of the state, promotes the concept of decentralisation and introduces the idea of ‘demarchy’. I quote:

In order to have democracy we must abandon elections, and in most cases referendums, and revert to the ancient principle of choosing by lot those who are to hold various public offices. Decision-making bodies should be statistically representative of those affected by their decisions. The illusory control exercised by voting for representatives has to be replaced by the chance of nominating and being selected as an active participant in the formulation of decisions. Elections, I shall argue, inherently breed oligarchies. Democracy is possible only if the decision-makers are a representative sample of the people concerned. I shall call a polity based on this principle a demarchy, using “democracy” to cover both electoral democracy and demarchy […..]

The whole tendency of demarchy is to replace the rigid legal electoral and administrative procedures of state democracy, which tend to standardize and atomize people, by flexible, responsive, participatory procedures that permit and foster maximum variety.

The whole last chapter is devoted to this concept of demarchy. He lists four conditions for its realisation:

- The first condition of demarchy being possible is that the society in which it is to be instituted be reasonably democratic in its social attitudes. While recognizing that people may differ greatly in particular abilities, the demarchist does not believe that there is any group of people whose capacities entitle them to a position of special or wide-ranging power in the community. At the base level choices made by people of no special ability are likely to be reasonable provided they are based on sound knowledge. They may need expert advice, but the judgement about whose advice to take is appropriately made by lay persons.

- The productive technology of the society must be ample to provide a good deal of time and resources that can be devoted to public debate and decision-making.

- People must value the opportunity for effective participation in matters that interest them and be prepared to leave other matters to those who have those interests, provided they are satisfied that the system is fair and effective.

- People must be anxious to avoid rigidity, bureaucracy and concentration of power. They must want to avoid giving power to the state if other social mechanisms will produce common goods reliably and fairly.

The book is too full of ideas to do them justice here. One particular gem that i want to include, because it is the expression of an essentially transhumanist view: “What human nature is is a matter of what human beings can do.”

The whole topic of Deliberative Democracy and this book in particular offer plenty of food for thought, and i highly recommend incorporating these ideas in discussing and developing a foundation for transhumanist politics.

3. Participism

As the name implies, this concept attempts to allow for determination by the people through active participation in both political and economical processes. These two branches are known separately as parpolity and parecon; their main proponents are Michael Albert, Robin Hahnel and Stephen R. Shalom. Instead of discussing these features here suffice it to describe them in the words of the authors.

In a short interview Shalom describes parpolity as

A type of direct democracy, using a system of nested councils. Everyone would be a member of a primary council, which would be small enough for face-to-face decision making and for real deliberation. Decisions that affected only or overwhelmingly the members of one of these councils would be made in that council. Decisions that affected more than the people in a single council would be made in a higher-level council that would consist of delegates from several lower-level councils. There would then be additional council layers as needed to accommodate the entire society. […..] There are other aspects of the Parpolity model—such as the High Council Court, a mechanism that attempts to protect the rights of minorities without (like the US Supreme Court) becoming an instrument of minority rule.

On parecon Hahnel says:

Parecon is a proposal or vision for how to accomplish economic functions consistent with classlessness, self-management, solidarity, equity, diversity, and ecological good sense. Parecon is not, however, a blueprint, but is rather a formulation of some critical attributes a few key aspects of economics need to have if we are to accomplish desirable aims. Beyond those critical attributes of key aspects, there is, of course, room for great diversity […..]

And what are parecon’s key aspects? First, workers and consumers self-managing councils, where self-management means people have a say in decisions proportionate to the extent they are affected by them […..]

The next key feature of parecon is called balanced job complexes. This names a new way of dividing tasks among jobs. In a participatory economy, you do a job, so do I, and so do all others who are of age and able to do work that contributes to society. More, we each choose a job that we wish to do […..] we define jobs so that each one includes a mix of tasks that convey, overall, roughly the same degree of empowerment as other balanced jobs convey to other workers […..]

The third defining feature of a participatory economy is a new norm for determining how much of the social output each member of society receives […..] people should get a share of the total social output in accord with the duration, intensity, and onerousness or socially valued labor that they do […..]

Finally, the last key aspect of parecon and the hardest to be brief about, is called participatory planning. This approach to allocation replaces markets and central planning, each of which directly violates central aims and values of parecon and each of which also generates class division and class rule […..] Very briefly, workers’ and consumers’ councils, which were mentioned earlier, cooperatively negotiate economic outcomes, without incurring undue costs in time allotted and in a manner conducive not only to self-management, but to the most informed choices possible. The procedures involve making proposals, assessing them, and refining them, all in light of steadily improving indications of true and full social and ecological costs and benefits, until arriving at a plan.

There are several books by each, Albert and Hahnel, and one by Shalom available at Amazon, as well as a graphic book titled Parecomic by Michael Wilson about the concept and about Albert in particular. A very rich source is the media group Z Communications, cofounded and coedited by Albert.

Deadlines prohibit me to deeply review all the material, but it certainly should be included in the discussion of our topic.

4. Others

There are many other ideas for improving the performance of current systems, more than i have space here to address. But i want to mention the work of Roberto Mangabeira Unger. In his idea of Empowered Democracy he emphasises the need for social experimentation and wants to see it given room within current polities in the expectation that once underway it will lead to progressive change. Much of his work can be viewed on and downloaded from his website.

J – Polystate

Even though Amon Twyman uses the term, as mentioned, to categorise ZS, i could not find any further references to it, except last year’s eponymous book by Zach Weinersmith. This is one of the most interesting ideas i have come across, especially in the transhumanist context as it deals with political constructs based in virtual spaces. Under the assumption that politics will be increasingly migrating into virtual spaces, as many other activities like business and the media already have done and are doing, i have approached the book from the perspective of looking for solutions not only for developing political theories and performing certain political functions such as voting, but for governance itself. However instead of internal political structures and functions it concentrates on problems of interstate relationships.

Weinersmith introduces these three concepts:

- Anthrostate – “A set of laws and institutions that govern the behavior of individuals, but which do not govern a behavior within geographic borders”.

- Geostate – This is a political entity defined by the fact that its governance usually extends over a fixed geographical area. This includes almost all current nation states.

- Polystate – “The polystate is the collection of anthrostates in a hypothetical human society”.

The central topic of the book is the anthrostate, and the relationships of multiple not necessarily compatible anthrostates within a polystate. Weinersmith assumes reasonably that the internal structures and functions as well as their underlying ideologies can vary wildly. About the concept itself he says: “I am not a proponent of this idea or a detractor”. The idea of ‘government of choice’ is not a new one. It is known under the concept of panarchism, first introduced by Paul Émile de Puydt in his 1860 paper ‘Panarchy’.

Unfortunately i let myself be misled into thinking that anthrostates as well as polystates are based within one or several geostates, probably because it is never explicitly stated that a polystate indeed is based within its own geographic area, and because ZS, the one polystate mentioned earlier, is obviously based within many geostates. Indeed at location 605 is this quote: “WS-1 [a hypothetical polystate] does not claim any territory”. But there are several other quotes i could list that seem to indicate that polystates can indeed have their own territory. This conflict is never really resolved.

Much of the book deals with relations between anthrostates, exploring ways in which problems resulting from incompatibilities in for instance economical, criminal, electoral and taxational laws can be resolved, including warfare. Under current conditions no geostate would cede authority in these matters or tolerate these conflicts within its territory.

As initially mentioned many transhumanist parties have sprung up across the globe, all aiming at participating in national elections except for one: TPV (transhumanist party virtual). This can not be a true party until it finds a state, such as an anthrostate, within which it could compete. However the two virtual states mentioned are not prepared for electoral democracy, and may not ever decide to be. As i know of no other virtual state that is, most likely because an established legislature would not have the power to implement any of the above mentioned policies within the territory of any geostate, and therefore would under current conditions be of limited utility, the whole issue remains hypothetical.

Indeed Weinersmith has described his book as a thought experiment, and as such i find it to be a good source of ideas. In a recent interview he refers to the “discretization of experience”, by which he means the increasing variety of choices for customers afforded by technology, which he extrapolates, very reasonably, to include choices for customers of government. In his book however he takes this idea to the point of having for instance an anarchist, a communist, a liberal and a fascist sharing the same house (possibly even the same apartment?) and living under different governments and laws. This shows the inherent weakness of the oxymoronic concept of virtual reality. There are only two ways in which it can be achieved: subjectively, by induced amnesia so that the subject is not aware of any reality outside the one he experiences, which is the model assumed by simulation theories, or objectively, by transitioning from physical existence into virtual existence as software while maintaining awareness of the existence of physical reality. Unless one accepts the esoteric concept of involution according to which the physical plane of existence emerged from the astral, and that in turn from the causal one, all nonphysical realities always remain rooted in the physical. To live within a computer its physical machinery must be maintained, protected and energised. The same is true for a virtual polystate, and sharing it with an IS militant would sooner or later lead to conflict not only between anthrostates but also involving the not so virtual reality of physical swords and bombs.

In conclusion it seems clear that Weinersmith does not offer or try to offer any real solutions to the problem of what used to be subcultures multiplying and consolidating in virtual spaces and reconciling their differences with the physical basis within which they operate. That will have to be, and is being, done by emerging virtual states, parties and other political bodies themselves. As for the objective of developing political structures congruent with transhumanist thought, he takes no position here.

Conclusion

Even though the presented constitutes a very limited sample, there is certainly no shortage of ideas, and there are some more elaborate models, out there that can and should be used in discussing and developing theories that will be coherent within a transhumanist framework. Transhumanist parties and their theoreticians have a big task ahead which is alleviated by agreement on common principles while giving room to accommodating different national conditions.

But i have been encouraged by seeing how many good brains have been working on these ideas for years already.

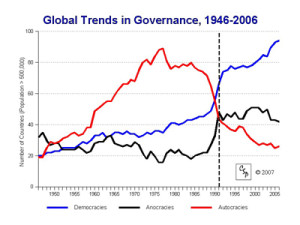

On this optimistic note i will leave the reader with an interesting historical observation published by the Center for Systemic Peace.

René Milan 2015-06-30

First published on the 20th of March 2015 on the as chapter 7 of Transpolitica Book 1: “Anticipating Tomorrow’s Politics“

July 4, 2015 at 8:55 pm

What about the Zeitgeist Movement? A lot of concrete proposals there.